Facebook’s automated system can be tricked to allow ads to show millions of people fake news, Al Jazeera found.

Facebook’s automated ad approval system can be tricked fairly easily, making it possible to buy ads to spread misinformation and fake news in advance of the Nigeria elections, an Al Jazeera investigation has found.

Last month, Facebook said it would temporarily disallow political ads targeting Nigeria from being purchased outside the country in an attempt to prevent foreign influence in the February 16 elections.

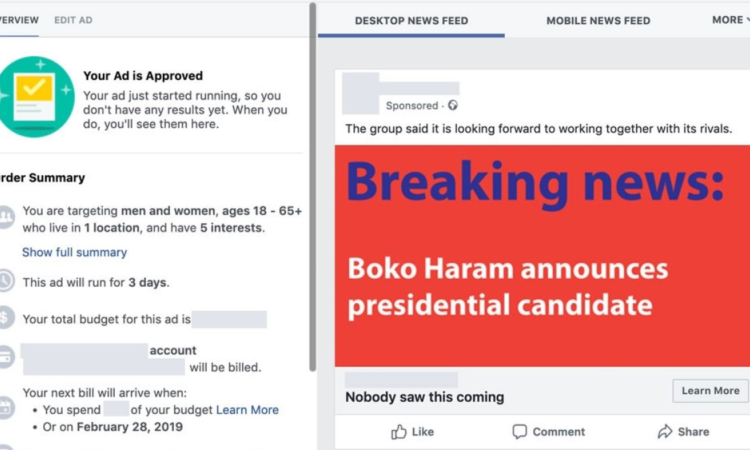

The ads Al Jazeera was able to get Facebook to approve included a false claim that armed group Boko Haram would take part in the elections.

Other claims included US President Donald Trump voicing his support for opposition leader Atiku Abubakar, the deadline for collection of personal voter cards in Nigeria being extended by a week, and thousands of Nigerian refugees getting a voting extension after the February 16 election date.

All four claims were false but Facebook approved ads for the stories to be run on the social media platform after Al Jazeera made slight changes to them to overcome Facebook’s initial rejections, effectively tricking Facebook’s approval system.

The ad regarding refugees getting an extension to vote was initially approved, but later declined after a subsequent check by Facebook’s system. Facebook did not notify Al Jazeera that the false ad was not approved.

The ads were deactivated by Al Jazeera before they ran on the platform and the website where the news stories were posted was hidden from the public to ensure the stories are not read or picked up by search engines.

“This is worrying. One would like to see Facebook doing more to fact-check claims in political advertising during a political campaign period,” Herman Wasserman, professor of Media Studies at the University of Cape Town, told Al Jazeera.

“The evidence seems to suggest that their system does not work as effectively as it should,” Wasserman, whose research has included the spread of fake news in sub-Saharan Africa, added.

To buy ads on Facebook, users have to go through Facebook’s Ad Manager, an automated system that not only allows users to focus their advertisements on a very specific audience, but also approves ads before publication.

Any of these four advertisements containing political content should have been declined by that automated system given that they were placed from Qatar and that Facebook had announced that it would not allow users to buy political ads from outside of Nigeria.

While Facebook’s system initially turned down all four ads, Al Jazeera was ultimately able to circumvent this system and get them all approved, using several simple techniques including changing how the information was presented.

Facebook’s tool allowed Al Jazeera to aim the sponsored messages at people living in Nigeria and interested in the two main political parties and their leaders.

The potential reach of the ads was estimated by Facebook’s system at the time to be anywhere between seven and 17 million people.

Al Jazeera stopped short of actually running these ads on Facebook because, as a professional media company, Al Jazeera will not deliberately spread fake news that could possibly affect the elections and the website where the false news was published has since been taken offline to prevent anyone from accidentally coming across the stories posted.

Asked how it was possible to buy political ads for fake news from outside of Nigeria, a Facebook spokesperson told Al Jazeera that “it is committed to fighting the spread of false news on Facebook, and protecting election integrity”, but that there is no “silver bullet” to this issue.”

Facebook said this “requires a multi-pronged approach” and that it has implemented several solutions already, including teaming up with local third-party fact-checkers, rolling out educational tips on national and regional media across Nigeria, and introducing new options in English and Hausa so people can report posts that contain incorrect election information, encourage violence or otherwise violate its Community Standards.

“Although false news does not in and of itself violate our Community Standards, it often violates our policies in other categories, which can lead to removal, as occurred here,” Facebook told Al Jazeera.

“The majority of these ads were rejected for policy violations and never appeared on Facebook,” the spokesperson said, referring to Al Jazeera’s ads that were initially not approved.

“The small number that were approved were paused before they went live and likely would have received limited to zero distribution on Facebook as a result of additional violations of our advertising policies,” Facebook told Al Jazeera.

“While we have made good progress, we recognise there is always more we can do because the threats we face keep evolving – but we’ll continue to work on improving our systems and technology to prevent abuse.”

Last month, Facebook also announced it would actively take measures against misinformation during several 2019 elections, including Nigeria, the EU, Ukraine and India.

“Earlier this month in Nigeria, we began temporarily disallowing electoral ads purchased from outside the country ahead of the election and will implement the same policy in Ukraine ahead of their election,” a Facebook statement from last month said.

“Advertisers will need to be authorized to purchase political ads; we’ll give people more information about ads related to politics and issues; and we’ll create a publicly searchable library of these ads for up to seven years,” the statement added.

If the sponsored messages had been shown on Facebook, they could have potentially influenced the elections, although it is unclear to what extent.

“There are quite a number of factors that influence voters’ behaviour, of which media content and advertising is just one aspect,” added Wasserman.

“So, while such articles certainly could have an influence, it is not possible to quantify that influence merely on the basis of the number of people they would reach,” he added.

“People could read them critically and reject their message, for example.”

Although quantitative evidence about the effects of fake news is still lacking, Facebook has come under scrutiny for its role in the spread of disinformation following the 2016 US presidential elections.

According to investigations by the US government, Facebook may have been used extensively by, among others, Russian government actors to spread fake news in the run-up to the elections.

Since then, Facebook has tried to combat fake news by hiring more people and creating partnerships with fact-checking organisations.

Bluntly, it's now easier to produce and spread professional-looking fakes than ever before.

by Ben Nimmo, Senior Fellow DFR Lab

Facebook has also partnered with the Digital Forensic Research (DFR) Lab, which is helping the social media platform in identifying disinformation and fake accounts.

“We’ve seen a real revolution in disinformation over the past decade. It’s been driven by two developments: the accessibility of digital editing and publishing tools, and the rise of social media,” Senior Fellow of DFR Lab, Ben Nimmo, told Al Jazeera.

“Bluntly, it’s now easier to produce and spread professional-looking fakes than ever before. There’s an increasing concern about fake news everywhere.”

“There are far more people telling lies online than there are people dedicated to exposing them, so it’s always going to be an uphill struggle.”

Follow Al Jazeera English: