In October last year, Jitender Kumar, a 20-year-old from Kapashera on the Delhi-Haryana border, bought a Redmi Note 4 phone and an Airtel data plan, his first exposure to the Internet. He writes mostly in Hindi, in Latin script, because writing in Devanagari “takes too long”, and he often stumbles over unknown English words.

“Pehli baar meri keypad speed nahin thi. Ek shabd mein paanch minute me likh paaya tha (The first time, my keyboard speed was very slow. It took me five minutes to write one word),” he says.

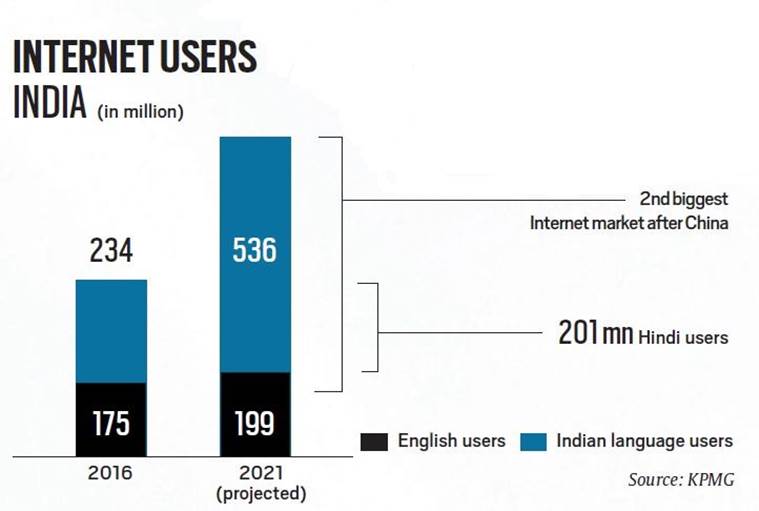

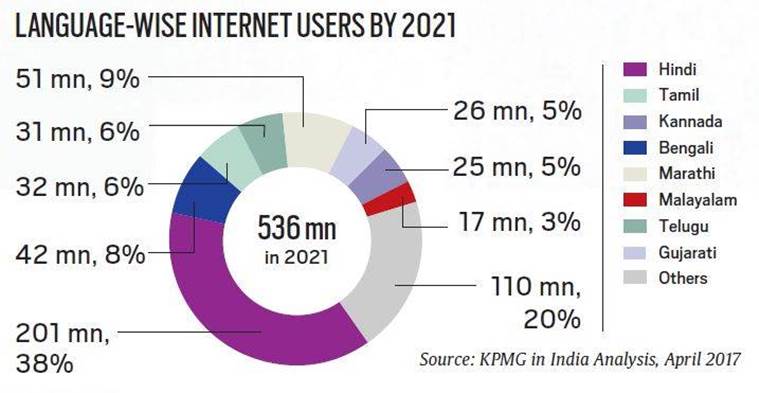

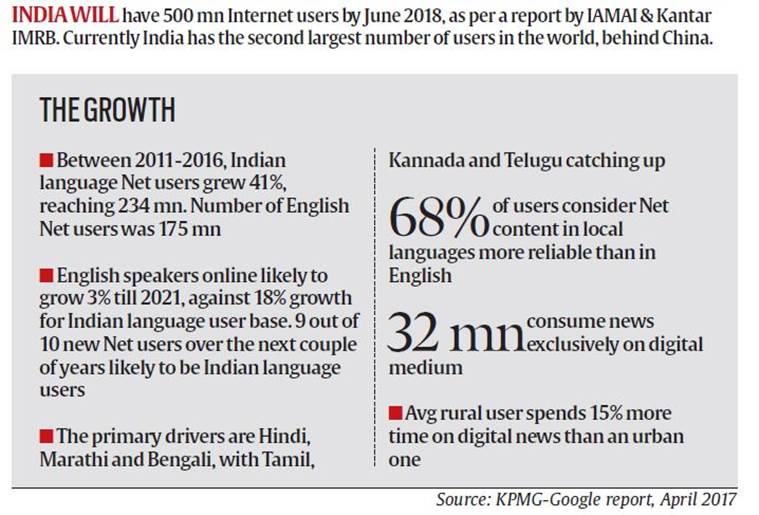

However, that didn’t deter Kumar. Neither is it stopping others across the country who prefer their primary language over English for communication. As per a Google-KPMG report, the Indian language user base surpasses that of English in the country, spurred by significant drops in smartphone and data prices. In the next couple of years, nine out of 10 new Internet users in India will prefer an Indian language, encompassing three-fourths of the country’s Internet user base, the report adds.

In the Internet sphere, they have a term for it — the Next Billion Users.

In a country with the second-largest number of Internet users in the world, these figures are significant at a time when one of the biggest challenges facing Internet growth is the spread of fake news, concerns over data security, privacy and information manipulation, and growth of hate speech — with the potential to disrupt election results. In his recent testimony before the US Senate, Mark Zuckerberg acknowledged these issues, adding that Facebook would do its best to protect the integrity of elections in India, its largest consumer base (more than 240 million users), with its increasingly fractious elections and its linguistic diversity.

“You need to understand what is a slur… not just in English, but a majority of people on Facebook use it in languages that are different across the world,” Zuckerberg said, emphasising the need for “local language support”.

Less than a week later, Facebook announced it was tying up with the Mumbai-based fact-checking organisation BoomLive for the May 12 Karnataka elections. BoomLive has one Kannada speaker and plans to hire one more, founder Govind Ethiraj says.

While the Cambridge Analytica scandal has forced Facebook to acknowledge an issue that has been knocking at its door for several years, political parties in India say they have been keeping an eye on social media in regional languages.

Divya Spandana, the Congress Social Media Head, says that tracking online misinformation “takes up much of (her) time”. “(BoomLive) should have local-language capacity because it’s easy to spread fake news in local languages,” she adds. “They don’t read Hindi, especially in the south. They don’t read English much. The more rural you go, they believe more easily because their exposure levels are lower.”

“A lot of fake news spreads in local languages — Kannada, Tamil, Marathi, etc,” says Y B Srivatsa, head of digital for the Congress in Karnataka.

The BJP too chimes in with similar concerns. “The challenge is going to be language in Karnataka,” says Tesjasvi Surya, the general secretary of the BJP Youth Wing in Karnataka, who is also overseeing the party’s digital communications in the coming state elections.

However, Amit Malviya, who is in charge of Information and Technology for the BJP, cautions that fake news measures could lead to “censorship by stealth”. “While it is Facebook’s prerogative to decide who to partner with,” he says, “what is Facebook’s core proposition? Are they a platform for expression, a content shop or a self-proclaimed vigilante?… Creating awareness to the idea of fake news will be a more lasting solution.”

Incidentally, less than one month ago, the Bengaluru police had arrested the owner of a website called postcard.news, Mahesh Hegde, on the charge of spreading fake news. Hegde is closely linked to right-wing Hindu outfits, has a BJP leader as his lawyer, was reportedly hopeful of a BJP ticket this time, and has been defended by senior BJP leaders.

As prime ministerial hopeful, Narendra Modi had been among the first political leaders in India to leverage social media efficiently by tapping into a demographic that didn’t speak English. One of the innovations adopted by his campaign team was messaging in different vernacular languages on Twitter.

As political parties find their feet in the Internet world, they will continue to run up against the conundrum of fake news and hate speech. Where does the lack of support for Indian language and content fit into this?

In 2016, KPMG and Google found that 60 per cent of Indian language Internet users found limited language support, primarily due to lack of content. As per an Internet & Mobile Association of India (IAMAI) study, the content of non-English Indian languages didn’t fare among the top 10 global languages used online as of 2016. In fact, Indian language content was a measly 0.1 per cent.

Findings from the IAMAI study also suggested that almost 43 per cent of non-computer users in rural markets and 13.5 per cent in urban might start accessing the Internet if content were available in their local language. In another indicator, it said that Hindi online content grew almost 95 per cent in 2015, against English content’s growth by 19 per cent.

Nishanth Sastry, King’s College of London researcher who has worked on online content consumption and dissemination in a US and Indian context, points out that the lack of content in Indian languages complicates misinformation issues, as users tend to drift more towards video and multimedia distribution, which is even more difficult to monitor.

Dona Sihi of FICCI’s Indian Languages Internet Alliance (ILIA) also notes the dramatic growth in audio-visual localisation.

As the Internet ecosystem turns its gaze to local languages though, the content is likely to grow more and faster.

“Till a couple of years back, businesses thought that non-English users were not their target audience,” says Rishi Kudale of Reverie Technologies, which has been aiding business and the Indian government in technology solutions since 2009, and has worked on projects such as BHIM. But as of two years ago, this myth was broken, he says. “Businesses now know they can’t ignore this at all.”

A research report by the company, which is yet to be released, shows that a little over 20 per cent of non-English users in India have a smartphone that costs more than Rs 11,000, crushing one of those myths — about the lack of a market in these languages. The primary drivers are Hindi, Marathi and Bengali, with Tamil and Kannada showing a high pace of Internet adoption, a KMPG-Google 2017 report said. Their study also found that those in rural areas spent more time on digital news consumption than their urban counterparts.

The upcoming Reverie report further found that over two-thirds of Indian language users now live in towns with populations under 1 lakh; only 6 per cent of the remaining live in metros with more than six million people.

For the last two years, as companies wake up to this reality, the starting point has been not why businesses must enter the non-English user market, but how, Kudale says. While chat and digital entertainment still take predominance, social media and digital news are gaining traction, along with digital payments, online government services, and digital classifieds.

In 2015, Farid Ahsan and others founded an Indian local language social network company called ShareChat to help new Internet adopters discover content and people. Ahsan says they deal with misinformation and hate speech with both algorithmic and human moderation. “We are better equipped to handle such challenges because we are focusing on lingual communities from day one,” he says, adding that they base their moderation on a content’s value to the community first, and then to the company.

Sihi points out that content generation also depends on factors such as advancements in natural language processing.

Google’s introductory translation technology of the late 2000s artificially broke up sentences to no more than five words and translated each segment separately, resulting in unnatural results, according to Head of Google Translate Barak Turovsky. By 2016, Google had improved this, now using neural networks to auto-translate. Broadly speaking, this process involves algorithms recognising patterns in translated documents and applying those findings. Indian usage of Google Translate grew 10 times in the last year, Turovsky says.

Standardisation organisations and government entities have also played a part. The Indian Standard Code for Information Interchange coded Indian languages that originate from Brahmi script in the late 1980s. The National Standard in script keyboard was designed in 1991. In 2016, the Internet Corporation of Assigned Names and Numbers developed a domain name system for Indian languages, and last year, the government announced that smartphones sold in India would have to support all 22 official languages.

The government push for technology in Indian languages has also come from the Technology Development for Indian Languages (TDIL), seeking language standardisation. The country also falls under Unicode, an international body that standardises linguistic characters for digital text.

In addition, a year ago, FICCI’s ILIA began working with stakeholders on standardising regulations and technology, as well as monetising the growth of Indian language content.

As user numbers surge though, some simple tasks are still not user-friendly. Email addresses, for example, says Kudale, remain mostly English-dominated.

But almost all researchers agree on what remains the main obstacle: data, data, data. While languages like English and German may be able to piggyback on several decades of data collection, most Indian languages lack the data required for increasingly data-dependent linguistic technology. “(This) is one of the biggest challenges in Indian languages,” Google’s Turovsky says.

Google India’s Gaurav Bhasker notes that while his company’s keyboard, GBoard, works with 300 languages, they face a challenge with those languages that “none of our in-house linguists may even be remotely familiar with”.

Santhosh Thottingal, who builds local language technology in India, says that building for Indian scripts is particularly difficult. “They have ligatures — shapes formed by fusing more than one letters. Sometimes vowel signs get attached to consonants. Consonants get stacked, fused and so on.”

Facebook-owned WhatsApp, a primary social media source in India with about 200 million monthly active users, presents another set of problems. The platform is encrypted for users, and therefore it becomes more difficult for researchers and fact-checkers to track the origins of misinformation, Sastry says.

“Human moderation is not going to scale to the volumes of content we are seeing on social media, so you do need artificial intelligence approaches,” he says. “But any AI is going to be a crude approximation of some patterns. Humans are inventive and creative. They will find ways to evade that.”

As technological players search for solutions, some voice a concern that is now coming to the fore in the wake of Cambridge Analytica. IIT-Bombay researcher Raji Ajwani-Ramchandani says a potential lack of digital literacy among non-English users exacerbates data privacy and security concerns. “These people may not even have the resources to fight back,” she says. “We don’t know where our data is going and we call ourselves English, educated users. What about these people?”

Sastry says the new phase of Internet adopters will not only lack the digital literacy to navigate the Web, but also face a more steep learning curve in a maturing Web.

Ajwani-Ramachandani also expresses concerns about increasing the desire for products in a population that still might not be able to afford them, potentially adding to problems such as farmer suicides. “One-sided” and “superficial” studies by people who haven’t spent any time with the people they are researching, she says, focus on increasing demand, “but don’t think if these people are in the position to pay.”

“I am not saying that they shouldn’t have choices and opportunities,” she says. “But the criteria of someone sitting in an IT job is very different from someone sitting in a village.”

Others raise more basic concerns of how negative emotions will be checked on social media in regional languages, with studies showing a tend to gravitate towards primary languages when expressing the same. Researchers at Microsoft have found that Hindi-English bilinguals prefer Hindi to express negative opinions and swearing on Twitter. “This is interesting because in that case, if you think of fake news… that is likely in Hindi,” says Monojit Choudhury, who was part of the study.

Around five months ago, BoomLive reported a video of drug cartel members ripping out a man’s entrails while he was alive, circulating on WhatsApp and Facebook. The caption, in Kannada, read: ‘In the name of Love Jihad, RSS men rip Muslim brother’s heart.’ Boom’s reverse image search found that the video was not even from India.

Sastry, who is from Bengaluru, says there are many dialects of his state that he himself cannot understand. Just having some Kannada speakers tracking content will not cover all dialects and variations, he notes.

Pratik Sinha, editor of Indian fact-checking organisation AltNews, acknowledges that if Facebook had tied up with his group instead of BoomLive for the Karnataka elections, they would not have had the capacity to tackle fake news in Kannada. “The issue is of magnitude,” he says. “AltNews and BoomLive can’t cope with all the fake news that is there, especially when it comes to different languages.”

Karishma Mehrotra… read more

Karishma Mehrotra… read more